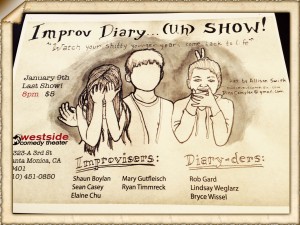

Last week, I participated in an improv comedy show here in LA at the M.I. Westside Comedy Theater. The theme of the show was diaries. I was one of three readers who shared a passage from their secret jottings in front of a large audience as a troupe of actors listened attentively. Once finished, the actors proceeded to do improvisational “alternate versions” of the passages, using the people, places and emotions revealed in the reading. The results were often hilarious.

I was the first to read. My passage, about meeting some women in Prague a few years ago,  was met with much laughter, but also some gasps at my unfiltered descriptions. Even as I read the diary entry, I cringed at some of the repeated references to a woman who had physical peculiarity that…well, you had to be there.

was met with much laughter, but also some gasps at my unfiltered descriptions. Even as I read the diary entry, I cringed at some of the repeated references to a woman who had physical peculiarity that…well, you had to be there.

In the same way, there are many anecdotes in my soon-to-be released book, “Distilling Rob: Manly Lies and Whisky Truths”, that make me squirm with palpable unease at their raw retelling. The diary reading the other night and the book have made me think about the connection between authenticity and audience in storytelling – no matter if that story is a fictional romance or if the story is what a person thinks about a particular whisky being reviewed.

Whenever someone new to writing asks me for advice, I always tell them to write, write, write. Don’t filter, don’t censor, and don’t write with fear. Never linger on a first draft. Leave concern over a particular paragraph, sentence, word or chapter for your rewrite. That first rush of emotion, reaction, relaying and relating is where the essence of one’s message lies. Rewriting refines the messages and themes.

Whisky bottling oftentimes utilizes a similar process. Chill filtering is a way to “clean-up” the story of the whisky during the bottling process. In the chill filtering process, whisky is chilled to near freezing to suspend certain sediments, esters, fatty acids and such. As a result, the whisky will not turn hazy when it is chilled or water is added by a person who drinks it. On the flip side, there is a strong sentiment that removing strong sediments also strips away some of the flavor in whisky. The eliminated flavor elements could add surprisingly nice depth to the whisky, or those flavors could harshly affect the enjoyment of the spirit. One doesn’t know without trying an unfiltered version of the whisky.

I’ve had plenty of whisky straight from the cask, and there’s something very connective about seeing charcoal residue in the bottom of your glass when you finish. You don’t feel like you simply had a dram of whisky (at cask strength nonetheless) but that you have ventured through the looking glass into the private world where wood and spirit interact for years to create whisky. Sometimes that journey leaves your mouth feeling gritty, and on occasion finds you spitting out a small piece of charred wood. But, there is never any regret about being exposed to something so rawly authentic.

I admire writers who aren’t afraid to let readers into their authentic world. Filtering words and descriptions might be easier on a writer’s soul and psyche, not to mention his or her inbox should readers respond with passionate disagreement. But, I firmly believe that readers respond to someone who is brave enough to expose the innermost thoughts and feelings.

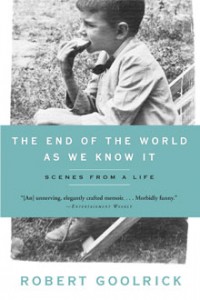

I read a memoir by the author Robert Goolrick in which he described how his often-drunk  father raped him as a child. Talk about taboos: incest, rape, sodomy and child abuse all there on the page for the world to see. I had the chance to talk to Goolrick a couple of years ago after hearing him read from the book at a writer’s conference. He was dazed by the reading. You could tell he didn’t want to share that story at all. His memoir likely shook the lives of family members and friends alike, perhaps even alienating some of them from his life. But, it was obvious he knew that the story needed to tell itself. Truth finds its way through the center of the best storytelling, both in fiction and nonfiction.

father raped him as a child. Talk about taboos: incest, rape, sodomy and child abuse all there on the page for the world to see. I had the chance to talk to Goolrick a couple of years ago after hearing him read from the book at a writer’s conference. He was dazed by the reading. You could tell he didn’t want to share that story at all. His memoir likely shook the lives of family members and friends alike, perhaps even alienating some of them from his life. But, it was obvious he knew that the story needed to tell itself. Truth finds its way through the center of the best storytelling, both in fiction and nonfiction.

I find the same truth-to-self reflected in two of my favorite whisky reviewing bloggers: Gal Granov and Sku’s Recent Eats. Their approach to whisky reviewing is uncompromising, which, for people who are not established whisky writers (as in, someone who can get away with saying something negative about whisky because they’re so big in the industry) is a brave thing. They risk being shut out of samples and invites to industry events, in other words, having access to the very thing they’re passionate about greatly reduced, if not eliminated, by whisky makers who are particularly sensitive to their reviews. Yet, those two consistently call things as they see them, sometimes drawing fierce disagreement from readers, but not disrespect.

As I stood on stage last week and heard nervous laughter and sensed squirming unease as I read certain parts of my diary, I was right there with the audience. I couldn’t believe this person said some of those things. I had the added embarrassment of knowing that person was me. Yet, I looked the audience members in the eye, let my words sink in, and moved on as I delivered more material with which the improv actors could skewer me.

We all, ideally, want others to see the best parts of ourselves. Life is much simpler when you don’t grate against people’s expectations and agendas. However, living or writing in that manner only fades unique voices into the cacophony of the masses. Individuals need to remain loyal to their truths, no matter how unpleasant or uncomfortable those truths may be for others. That’s not to say adherence to one’s authenticity gives a person license to disrespect those who may hear or read one’s words. Be true, but don’t be a jerk about it (ahem, talk radio hosts).

When you remain sincere to yourself, you express the truths, good and bad, in each of us, which is something people can relate to and respect. How you filter and refine that truth is up to you as a person or a writer. But, you can never lose sight of it.

Rob, I needed to read this post today. Sometimes I doubt myself and my abilities. I compare myself to other writers instead of just focusing on my writing and my truth.

I’m glad you read it at the right time for you. Sometimes I look at what I’ve put on a page and all I see is a jumble of meaningless words, and I think I’m an absolutely awful writer that is bland and I make no sense. But, when you stick to the truth of your storytelling, you will work through those bumps and find a way to reconnect to what you need to say.