At some point, within the first five minutes of finding out I write about whisky, people inevitably ask me what my favorite whisky is. As I’ve stated here many times before, I can honestly say the best whisky is the one you’re drinking when you stop and say, “I love this moment.” I gave an impromptu whisky tasting in Caen, France last week, and I didn’t have much variety in whiskies with me, but the Laphroaig 10-year-old was perfect in that moment, with the gentle rain and the French music.

Highland Park produces one of the best single malts available.

Once I explain my thoughts about the best whisky, I always follow up with this: even though the best whisky is the one you’re drinking at a particularly fine moment, I always have several bottles of Highland Park 18-year-old in my cabinet. Why several bottles? Well, it’s really so good I never want to be caught short of it.

With that in mind, I made the journey to Scotland’s Orkney islands last month to spend time talking with Highland Park Distillery Manager Russell Anderson and to tour the more than 200-year-old distillery that produces, in my opinion, the perfect dram in the 18-year-old.

The Orkney islands are an aberration for Scotland. The island chain was in the Nordic realms until 400 some years ago, and even now it feels more like its own country in some ways because of that heritage. Gaelic influence, which is readily felt in places like Islay or Skye, seems absent in Orkney except in the very vital area of whisky distillation. The Orkney main island is surrounded by rugged waters that have time and again seen the impact of history, from Neolithic times and the 5,000 year old house remains at Skara Brae village to the submerged German WWI fleet in the Scapa Flow.

My goal was to learn less about epochs of time and more about the relatively short term time it takes to produce a good Highland Park: 12, 15, 18, 30 years or whatever it may be. Island distilleries must be fairly independent and innovative with their processes due to their remoteness from the Scottish mainland. When issues arise all they have are the resources at hand to utilize for their production.

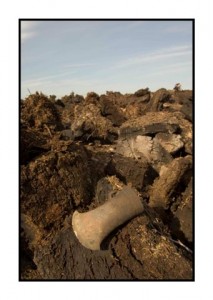

For Highland Park (www.highlandpark.co.uk), those resources mean harvesting their own peat from land near their location in Kirkwall. According to Russell, the peat is critical to Highland Park’s flavor profile. They’ve experimented with other peat, even peat from elsewhere in the Orkneys, and the subtle differences in vegetation make for a major change in the end product. So, for six months out of the year their peat cutting team is hard at work harvesting the catalyst for the distillery’s own floor maltings.

Cutting one’s own peat and doing one’s own maltings is not inexepensive for a distillery that produced 2.5 million litres last year. However, Russell says he holds his own ground against any accountants who question those higher costs.

“It’s about maintaining quality and it’s quite an expensive product to produce,” he says. “But, I’m absolutely convinced that the extra cost is critical for quality.”

A walk through the distillery seems like a walk through time, as the original stone buildings and cobblestone paths make Highland Park look like a living history museum. Despite being on a relatively remote island far removed from any major city, Highland Park receives thousands of visitors every year. Most know and love the malt, which makes their visit a pilgrimage of sorts. I have to say, I felt the same way.

“I still to this day find it extremely humbling for people to come from all over the world to see the distillery. It’s my day job,” Russell says.

Each Highland Park expression has a different balance of Orkney peatiness, barley maltiness and fermented sweetness. For me, and for Russell, the 18-year-old is the perfect culmination of that balance. The 18-year-old uses a higher percentage of sherry casks than younger offerings to bring a spicy sweetness to the marriage of oak and peat. Put simply, everything is right with the 18-year-old. Nothing can make it any better, and every time I have a sip I have the same amazed reaction.

Russell and his team work very hard to keep Highland Park’s 210-year-old tradition of excellence strong. For a distillery with such a large output, there is considerable care and attention to detail in the production process. The result is a whisky that is produced in enough quantity to reach discriminating consumers around the world and is delivered with enough quality to keep them coming back for more.

work on a secret project that would forever change the course of history: I will call it the Manhattan Project. No, not THAT Manhattan Project! The only way to get bombed with the product of this Manhattan Project is to say, “Bartender, can I have another?” too many times.

work on a secret project that would forever change the course of history: I will call it the Manhattan Project. No, not THAT Manhattan Project! The only way to get bombed with the product of this Manhattan Project is to say, “Bartender, can I have another?” too many times. in this case, inside the barrel, to enhance the cocktail experience. I know I’m eager to try this concoction and may have to make the drive to San Diego at some point this summer.

in this case, inside the barrel, to enhance the cocktail experience. I know I’m eager to try this concoction and may have to make the drive to San Diego at some point this summer.